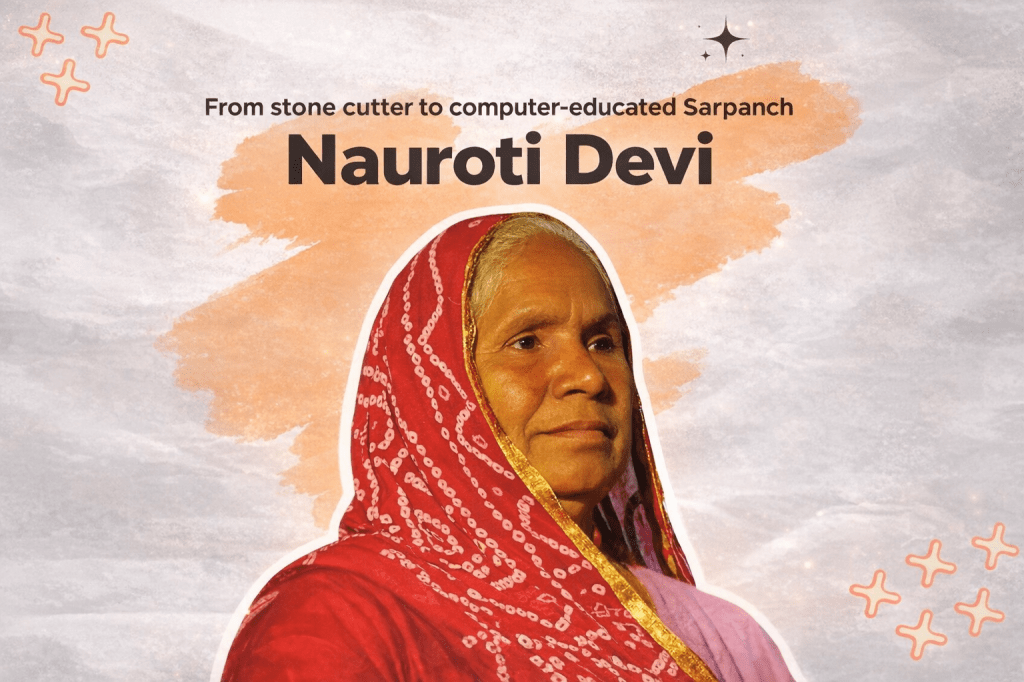

In the famine-scorched landscape of Kishangarh, Rajasthan, in 1981, survival depended on how much stone one could break under a relentless sun. Thousands of rural labourers—many of them Dalit women—worked at road construction sites, paid irregularly and unequally. Among them was Nauroti Devi, an illiterate stonecutter whose life was governed by rules she could neither read nor question. Few would have imagined that this woman would later digitise village governance and emerge as a key figure in India’s grassroots transparency movement.

Her journey from quarry labour to institutional leadership is not a story of individual uplift alone. It is a case study in grassroots leadership, decentralised governance, and the role of digital capability in democratising power.

From Wage Exploitation to Legal Assertion

Nauroti Devi’s political consciousness emerged from everyday injustice. During famine relief work, women were paid less than men, and wages were often withheld on subjective grounds of “poor work quality.” Rather than accepting this as routine exploitation, she organised nearly 700 labourers across five villages and escalated the issue beyond local authorities to the Supreme Court of India.

The judgment in favour of the workers was a landmark moment. Yet for Nauroti, the victory was incomplete. It revealed a structural weakness: the dependence of the poor on educated intermediaries to interpret laws and documents. Illiteracy, she realised, was not merely the absence of schooling—it was the absence of autonomy. This insight marked her transition from protest-based resistance to a sustained pursuit of institutional power.

Learning as Political Strategy

Determined to eliminate this dependency, Nauroti turned to learning later in life. At Barefoot College, Tilonia, where she worked as a saathin for women’s empowerment, she embraced literacy and digital skills in her fifties—an age when learning is socially discouraged, especially for rural women.

She refused to view technology as elite territory. To her, a computer was simply a man-made machine and therefore learnable. Free from fear and intimidation, she mastered basic applications and internet use, eventually training others—including government functionaries. Her experience demonstrated that the primary barrier to digital inclusion is not age or qualification, but psychological exclusion.

Digitising the Panchayat: Governance in Practice

Elected sarpanch of Harmada Gram Panchayat in 2010, Nauroti Devi applied these skills to everyday governance. She introduced digital record-keeping, computerised notices, and systematic documentation in the panchayat office. This administrative discipline reduced delays, limited manipulation, and improved institutional efficiency.

Crucially, digital governance translated into tangible outcomes. During her tenure, she reclaimed encroached land meant for a government health centre, defended communal property, confronted entrenched criminal interests, and expanded basic infrastructure such as toilets, hand pumps, and housing for the poor. By the end of her term, the panchayat recorded a financial surplus—an uncommon outcome in rural administration—reflecting transparency and fiscal discipline.

Here, technology functioned not as symbolic modernisation, but as a tool of accountability.

Information as Power: The RTI Connection

Long before holding office, Nauroti Devi had been associated with the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), the grassroots movement that laid the foundation for India’s Right to Information Act. Having experienced exclusion from official records, she understood that information was not an abstract right but a political weapon for the poor.

Her effectiveness within the RTI movement stemmed from lived experience. She recognised that access to documents could alter power relations between citizens and the state, especially in rural areas where opacity enables exploitation.

Credentialism versus Democratic Capability

In 2015, the Rajasthan Panchayati Raj Amendment introduced minimum educational qualifications for contesting local elections. Despite decades of public service, digital literacy training, transparent financial management, and institutional leadership, Nauroti Devi was rendered ineligible to seek re-election.

The episode highlighted a fundamental tension in Indian democracy: the prioritisation of formal certification over demonstrated capability. Rather than professionalising local governance, the law narrowed democratic participation by excluding precisely those leaders who had emerged from lived experience and grassroots legitimacy.

Why Nauroti Devi’s Story Matters

Nauroti Devi’s life challenges the assumption that leadership capacity flows automatically from formal education. Her journey—from stone-cutting sites to digital governance—illustrates that agency, access to information, and confidence to engage institutions are often more decisive than credentials.

For UPSC and policy discourse, her story intersects key themes: social justice, decentralisation, digital governance, transparency, and substantive democracy. More importantly, it reminds us that empowerment succeeds not when institutions merely include the marginalised, but when people acquire the capacity to engage power without fear.

We welcome your feedback